Zeila

Zeila

| |

|---|---|

Town | |

| Coordinates: 11°21′14″N 43°28′23″E / 11.35389°N 43.47306°E | |

| Country | |

| Region | Awdal |

| District | Zeila District |

| Established | ca. 1st century CE |

| Population (2012) | |

• Total | 18,600[1] |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (EAT) |

| Climate | BWh |

Zeila (Somali: Saylac, Arabic: زيلع, romanized: Zayla), also known as Zaila or Zayla, is a historical port town in the western Awdal region of Somaliland.[2]

In the Middle Ages, the Jewish traveller Benjamin of Tudela identified Zeila with the Biblical location of Havilah.[3] Most modern scholars identify it with the site of Avalites mentioned in the 1st-century Greco-Roman travelogue the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea and in Ptolemy, although this is disputed.[4][5] The town evolved into an early Islamic center with the arrival of Muslims shortly after the Hijrah. By the 9th century, Zeila was the capital of the early Adal Kingdom and Ifat Sultanate in the 13th century, it would attain its height of prosperity a few centuries later in the 16th century. The city subsequently came under Ottoman and British protection in the 18th century.

Up until recently Zeila was surrounded by a large wall with five gates: Bab al Sahil and Bab al-jadd on the North. Bab Abdulqadir on the East: Bab al-Sahil on the west and Bab Ashurbura on the south.[6]

Zeila falls in the traditional territory of the ancient Somali Dir clan. The town of Zeila and the wider Zeila District is inhabited by the Gadabuursi and Issa, both subclans of the Dir clan family.[7][8][9][10]

Geography

Zeila is situated in the Awdal region in Somaliland. Located on the Gulf of Aden coast near the Djibouti border, the town sits on a sandy spit surrounded by the sea. It is known for its coral reef, mangroves and offshore islands, which include the Sa'ad ad-Din archipelago named after the Somali Sultan Sa'ad ad-Din II of the Sultanate of Ifat.[11] Landward, the terrain is unbroken desert for some fifty miles. Borama lies 151 miles (243 km) southeast of Zeila, Berbera lies 170 miles (270 km) east of Zeila, while the city of Harar in Ethiopia is 200 miles (320 km) to the west. The Zeila region named after this port city denoted the entire Muslim inhabited domains in medieval Horn of Africa.[12]

Foundation

Zeila, along with Mogadishu and other Somali coastal cities, was founded upon an indigenous network involving hinterland trade, which happened even before significant Arab migrations or trade with the Somali coast. That goes back approximately four thousand years.

According to textual and archeological evidence, Zeila, was founded by Sh. Saylici was one of many small towns developed by the Somali pastoral and trading communities which flourished through the trade that gave birth to other coastal and hinterland towns such as Heis, Maydh, and Abasa, Awbare, Awbube, Amud in the Borama area, Derbiga Cad Cad, Qoorgaab, Fardowsa, Maduna, Aw-Barkhadle in the Hargeisa region and Fardowsa, near Sheikh.[13]

Ancient Zeila was divided into five residential districts; Khoor-doobi, Hafat al-Furda, Asho Bara, Hafat al-Suda and Sarrey.[14]

History

Avalites

Zeila is an ancient city and has been identified with the trade post referred to in classical antiquity as Avalites (Greek: Αβαλίτες), situated in the region of Barbara in Northeast Africa. During antiquity, it was one of many city-states that engaged in the lucrative trade between the Near East (Phoenicia, Ptolemaic Egypt, Greece, Parthian Persia, Saba, Nabataea, Roman Empire, etc.) and India. Merchants used the ancient Somali maritime vessel known as the beden to transport their cargo.[15]

Along with the neighboring Habash of Al-Habash to the west, the Barbaroi who inhabited the area were recorded in the 1st century CE Greek document the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea as engaging in extensive commercial exchanges with Egypt and pre-Islamic Arabia. The travelogue mentions the Barbaroi trading frankincense, among various other commodities, through their port cities such as Avalites. Competent seamen, the Periplus' author also indicates that they sailed throughout the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden for trade. The document describes the Barbaroi's governance system as decentralized and essentially consisting of a collection of autonomous city-states.[16] It also suggests that "the Berbers who live in the place are very unruly,"[17] an apparent reference to their independent nature.[16]

Ifat & Adal Sultanates

Islam was introduced to the area early on from the Arabian Peninsula, shortly after the Hijrah. Zeila's two-mihrab Masjid al-Qiblatayn dates to the 7th century, and is the oldest mosque in the city.[18] In the late 9th century, Al-Yaqubi wrote that Muslims were living along the northern Somali seaboard.[19] He also mentioned that the Adal kingdom had its capital in the city,[19][20] suggesting that the Adal Sultanate with Zeila as its headquarters dates back to at least the 9th or 10th centuries. According to I.M. Lewis, the polity was governed by local dynasties consisting of Somalized Arabs or Arabized Somalis, who also ruled over the similarly-established Sultanate of Mogadishu in the Benadir region to the south. Adal's history from this founding period would be characterized by a succession of battles with neighbouring Abyssinia.[20]

By the years (1214–17), Ibn Said referred to both Zeila and Berbera. Zeila, as he tells us, was a wealthy city of considerable size and its inhabitants were completely Muslim. Ibn Said's description gives the impression that Berbera was of much more localized importance, mainly serving the immediate Somali hinterland while Zeila was clearly serving more extensive areas. But there is no doubt that Zeila was also predominantly Somali, and Al-Dimashqi, another thirteen-century Arab writer, gives the city name its Somali name Awdal (Adal), still known among the local Somali. By the fourteen century, the significance of this Somali port for the Ethiopian interior increased so much so that all the Muslim communities established along the trade routes into central and south-eastern Ethiopia were commonly known in Egypt and Syria by the collective term of "the country of Zeila."[21]

Historian Al-Umari in his study in the 1340s about the history of Awdal, the medieval state in western and northern parts of historical Somalia and some related areas, Al-Umari of Cairo states that in the land of Zayla’ (Awdal) “they cultivate two times annually by seasonal rains … The rainfall for the winter is called ‘Bil’ and rainfall for the ‘summer’ is called ‘Karam’ in the language of the people of Zayla’ [Awdali Somalis].”

The author’s description about seasons generally corresponds to the local seasons in historical Awdal where Karan or Karam is an important rainy season at the beginning of the year. The second half of the year is called ‘Bilo Dirir’ (Bil = month; Bilo = months). It appears that the historian was referring, in one way or another, to these still used terms, Karan and Bil. This indicates that the ancient Somali solar calendar citizens of Zeila were using was very similar to the one they use today. This also gives further credence that the medieval inhabitants of Zeila were predominantly Somali, spoke Somali, and had Somali farming practices.[22]

In the following century, the Moroccan historian and traveller Ibn Battuta describes the city being inhabited by Somalis, followers of the Shafi‘i school, who kept large numbers of camels, sheep and goats. His description thus indicates both the ingenious nature of the city, as indicated by the composition of its population, and, by implication through the presence of the livestock, the existence of the nomads in its vicinity. He also describes Zeila as a big metropolis city and many great markets filled with many wealthy merchants.[23] Zeila has also been known to be home to a number of Hanafis, but no research has been conducted as to how large the Hanafi population was in premodern Zeila.[24]

Through extensive trade with Abyssinia and Arabia, Adal attained its height of prosperity during the 14th century.[25] It sold incense, myrrh, slaves, gold, silver and camels, among many other commodities. Zeila had by then started to grow into a huge multicultural metropolis, with Somalis (Predominantly), Afar, Harari, and even Arabs and Persian inhabitants. The city was also instrumental in bringing Islam to the Oromo and other Ethiopian ethnic groups.[26]

In 1332, the Zeila-based King of Adal was slain in a military campaign aimed at halting the Abyssinian Emperor Amda Seyon's march toward the city.[27] When the last Sultan of Ifat, Sa'ad ad-Din II, was also killed by Dawit I of Ethiopia in Zeila in 1410, his children escaped to Yemen, before later returning in 1415.[28] In the early 15th century, Adal's capital was moved further inland to the town of Dakkar, where Sabr ad-Din II, the eldest son of Sa'ad ad-Din II, established a new base after his return from Yemen.[29][30] Adal's headquarters were again relocated the following century, this time to Harar. From this new capital, Adal organised an effective army led by Imam Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi (Ahmad "Gurey" or "Gran") that invaded the Abyssinian empire.[30] This campaign is historically known as the Conquest of Abyssinia (Futuh al Habash). During the war, Imam Ahmad pioneered the use of cannons supplied by the Ottoman Empire, which he imported through Zeila and deployed against Abyssinian forces and their Portuguese allies led by Cristóvão da Gama.[25] Some scholars argue that this conflict proved, through their use on both sides, the value of firearms like the matchlock musket, cannons and the arquebus over traditional weapons.[31]

I. M. Lewis gives an invaluable reference to an Arabic manuscript on the history of the Gadabuursi Somali. ‘This Chronicle opens’, Lewis tells us, ‘with an account of the wars of Imam ‘Ali Si’id (d. 1392) from whom the Gadabuursi today trace their descent, and who is described as the only Muslim leader fighting on the western flank in the armies of Se’ad ad-Din, ruler of Zeila.[32]

I. M. Lewis (1959) states:

"Further light on the Dir advance and Galla withdrawal seems to be afforded by an Arabic manuscript describing the history of the Gadabursi clan. This chronicle opens with an account of the wars of Imam ‘Ali Si’id (d. 1392), from whom the Gadabursi today trace their descent and who is described as the only Muslim leader fighting on the Western flank in the armies of Sa'd ad-Din (d. 1415), ruler of Zeila."[33]

Legendary Arab explorer Ahmad ibn Mājid wrote of Zeila and other notable landmarks and ports of the northern Somali coast during the Adal Sultanate period, including Berbera, Siyara, the Sa'ad ad-Din islands aka the Zeila Archipelago, El-Sheikh, Alula, Ruguda, Maydh, Heis and El-Darad.[34]

Travellers' reports, such as the memoirs of the Italian Ludovico di Varthema, indicate that Zeila continued to be an important marketplace during the 16th century,[35] despite being sacked by the Portuguese in 1517 and 1528. Later that century, separate raids by nomads from the interior eventually prompted the port's then ruler, Garad Lado, to enlist the services of 'Atlya ibn Muhammad to construct a sturdy wall around the city.[36] Zeila, however, ultimately began to decline in importance following the short-lived conquest of Abyssinia.[25]

Early Modern Period

16th-century Zeila, along with several other settlements on the East African coast, had been visited by the Portuguese explorer and writer Duarte Barbosa, describing the city as such: "Having passed this town of Berbara, and going on, entering the Red Sea, there is another town of the Moors, which is named Zeyla, which is a good place of trade, whither many ships navigate and sell their clothes and merchandise. It is very populous, with good houses of stone and white-wash and good streets; the houses are covered with terraces, the dwellers in them are black. They have many horses and breed many cattle of all sorts, which they use for milk, butter, and meat. There is in this country abundance of wheat, millet, barley, and fruits, which they carry thence to Aden."[37]

Beginning in 1630, the city became a dependency of the ruler of Mocha, who, for a small sum, leased the port to one of the office-holders of Mocha. The latter, in return, collected a toll on its trade. Zeila was subsequently ruled by an Emir, whom Mordechai Abir suggested had "some vague claim to authority over all of the Sahil, but whose real authority did not extend very far beyond the walls of the town." Assisted by cannons and a few mercenaries armed with matchlocks, the governor succeeded in fending off incursions by both the disunited nomads of the interior, who had penetrated the area, as well as brigands in the Gulf of Aden.[38] By the first half of the 19th century, Zeila was a shadow of its former self, having been reduced to "a large village surrounded by a low mud wall, with a population that varied according to the season from 1,000 to 3,000 people."[39] The city continued to serve as the principal maritime outlet for Harar and beyond it in Shewa. However, the opening of a new sea route between Tadjoura and Shewa cut further into Zeila's historical position as the main regional port.[40]

Haji Sharmarke and Pre Colonial Period

Sharifs of Mocha exercised nominal rule on behalf of the Ottoman Empire over Zeila.[41]

Hajji Sharmarke Ali Saleh came to govern Zeila after the Turkish governor of Mocha and Hodeida handed governorship from Mohamed El Barr to him.[42] Mohamed El Barr would not leave peacefully and Sharmarke departed for Zeila with a contingent of fifty Somali musketeers and two cannons. Arriving outside the city, he instructed his men to fire the cannons close to the walls. Intimidated and not having seen such weapons before, El Barr and his men would flee and leave Zeila for Sharmarke. Sharmarke's governorship had an instant effect on the city, as he maneuvered to monopolize as much of the regional trade as possible, with his sights set as far as Harar and the Ogaden.[43] In 1845, he deployed a few matchlock men to wrest control of neighboring Berbera from that town's then feuding Somali authorities. The Emir of Harar Ahmad III ibn Abu Bakr already been at loggerheads with Sharmarke over fiscal matters. He was concerned about the ramifications that these movements might ultimately have on his own city's commerce. The Emir consequently urged Berbera's leaders to reconcile and mount a resistance against Sharmarke's troops in 1852.[44] Sharmarke was later succeeded as Governor of Zeila by Abu Bakr Pasha, a local Afar statesman in 1855 but would return and depose Abu Bakr in 1857 before finally being ousted in 1861 after Sharmarke's implication in the death of a French Consul.[45][46]

In 1874–75, the Egyptians obtained a firman from the Ottomans by which they secured claims over the city. At the same time, the Egyptians received British recognition of their nominal jurisdiction as far east as Cape Guardafui.[47] In actuality, however, Egypt had little authority over the interior. Their period of rule on the coast was brief, lasting only a few years (1870–84). When the Egyptian garrison in Harar was evacuated in 1885, Zeila became caught up in the competition between the Tadjoura-based French and the British for control of the strategic Gulf of Aden littoral.

British and French Interest

On 25 March 1885, the French government claimed that they signed a treaty with Ughaz Nur II of the Gadabuursi placing much of the coast and interior of the Gadabuursi country under the protectorate of France. The treaty titled in French, Traitè de Protectorat sur les Territoires du pays des Gada-Boursis, was signed by both J. Henry, the Consular Agent of France and Dependencies at Harar-Zeila, and Nur Robleh, Ughaz of the Gadabuursi, at Zeila on 9 Djemmad 1302 (March 25, 1885). The treaty states as follows (translated from French):

"Between the undersigned J. Henry, Consular Agent of France and Dependencies at Harrar-Zeilah, and Nour Roblé, Ougasse of the Gada-boursis, independent sovereign of the whole country of the Gada-boursis, and to safeguard the interests of the latter who is asking for the protectorate of France,

It was agreed as follows:

Art. 1st – The territories belonging to Ougasse Nour-Roblé of the Gada-boursis from "Arawa" to "Hélo" from "Hélô" to Lebah-lé", from "Lebah-lé" to "Coulongarèta" extreme limit by Zeilah, are placed directly under the protection of France.

Art. 2 – The French government will have the option of opening one or more commercial ports on the coast belonging to the territory of the Gada-boursis.

Art. 3 The French government will have the option of establishing customs in the posts open to trade, and on the points of the borders of the territory of the Gada-boursis where it deems it necessary. Customs tariffs will be set by the French government, and the revenues will be applied to public services.

Art. 4 – Regulations for the administration of the country will be elaborated later by the French government. In agreement with the Ougasse of the Gada-boursis they will always be revisable at the will of the French government, a French resident may be established on the territory of the Gada-boursis to sanction by his presence the protectorate of France.

Art. 5 – The troops and the police of the country will be raised among the natives, and will be placed under the superior command of an officer designated by the French government. Arms and ammunition for the native troops may be provided by the French government and their balance taken from the public revenues, but, in case of insufficiency, the French government may provide for them.

Art. 6 – The Ougasse of the Gada-boursis, to recognize the good practices of France towards it, undertakes to protect the caravan routes and mainly to protect French trade, throughout the extent of its territory.

Art. 7 – The Ougasse of the Gada-boursis undertakes not to make any treaty with any other power, without the assistance and consent of the French government.

Art. 8 – A monthly allowance will be paid to the Ougasse of the Gada-boursis by the French government, this allowance will be fixed later, by a special convention, after the ratification of this treaty by the French government.

Art. 9 – This treaty was made voluntarily and signed by the Ougasse of the Gada-boursis, which undertakes to execute it faithfully and to adopt the French flag as its flag.

In witness whereof the undersigned have affixed their stamps and signatures.

J.Henry

Signature of Ougasse

Done at Zeilah on 9 Djemmad 1302 (March 25, 1885)."

— Traité de protectorat de la France sur les territoires du pays des Gada-boursis, 9 Djemmad 1302 (March 25, 1885), Zeilah.[49]

The French claimed that the treaty with the Ughaz of the Gadabuursi gave them jurisdiction over the entirety of the Zeila coast and the Gadabuursi country.[50]

However, the British attempted to deny this agreement between the French and the Gadabuursi citing that that Ughaz had a representative at Zeila when the Gadabuursi signed their treaty with the British in December of 1884. The British suspected that this treaty was designed by the Consular Agent of France and Dependencies at Harrar-Zeila to circumvent British jurisdiction over the Gadabuursi country and allow France to lay claim to sections of the Somali coast. There was also suspicion that Ughaz Nur II had attempted to cause a diplomatic row between the British and French governments in order to consolidate his own power in the region.[51]

According to I. M. Lewis, this treaty clearly influenced the demarcation of the boundaries between the two protectorates, establishing the coastal town of Djibouti as the future official capital of the French colony:

"By the end of 1885 Britain was preparing to resist an expected French landing at Zeila. Instead, however, of a decision by force, both sides now agreed to negotiate. The result was an Anglo-French agreement of 1888 which defined the boundaries of the two protectorates as between Zeila and Jibuti: four years later the latter port became the official capital of the French colony."[52]

British Somaliland

On 9 February 1888, France and Britain concluded an agreement defining the boundary between their respective protectorates.[53] As a result, Zeila and its eastern neighbor Berbera came to be part of British Somaliland.

The construction of a railway from Djibouti to Addis Ababa in the late 19th century continued the neglect of Zeila.[54] At the beginning of the next century, the city was described in the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica as having a "good sheltered anchorage much frequented by Arab sailing craft. However, heavy draught steamers are obliged to anchor a mile and a half from the shore. Small coasting boats lie off the pier and there is no difficulty in loading or discharging cargo. The water supply of the town is drawn from the wells of Takosha, about three miles distant; every morning camels, in charge of old Somali women and bearing goatskins filled with water, come into the town in picturesque procession. ... [Zeila's] imports, which reach Zaila chiefly via Aden, are mainly cotton goods, rice, jowaree, dates and silk; the exports, 90% of which are from Abyssinia, are principally coffee, skins, ivory, cattle, ghee and mother-of-pearl".[54]

Buralle Robleh the subinspector of police of Zeila was described by Major Rayne as one of the most important men in Zeila along with 2 others. He is featured on the image to the right with General Gordon, Governor of British Somaliland.[55]

In August 1940, Zeila was captured by advancing Italian troops. It would remain under their occupation for over six months.

Early Folk Music

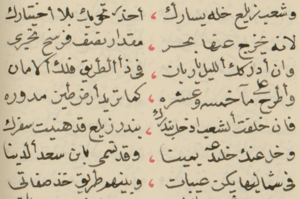

The famous Austrian explorer and geographer, P. V. Paulitschke, mentioned that in 1886, the British General and Assistant Political Resident at Zeila, J. S. King, recorded a famous Somali folk song native to Zeila and titled: "To my Beloved", which was written by a Gadabuursi man to a girl of the same tribe. The song became hugely popular throughout Zeila despite it being incomprehensible to the other Somalis.

Philipp Paulitschke (1893) mentions about the song:

"To my Beloved: Ancient song of the Zeilans (Ahl Zeila), a mixture of Arabs, Somâli, Abyssinians and Negroes, which Major J. S. King dictated to a hundred-year-old man in 1886. The song was incomprehensible to the Somâl. It is undoubtedly written by a Gadaburssi and addressed to a girl of the same tribe."[56]

Lyrics of the song in Somali translated to English:

Inád dor santahâj wahân kagarân difta ku gutalah. |

Noticing your offbeat rhythm, likely from your heavy steps. |

| —To My Beloved[57] |

Present

On 9 February 1991, the Somali National Movement (SNM) clashed with Djiboutian-backed USF forces on the Djiboutian border,[58][59] with the Issa USF forces, backed by former Somalian regulars, occupying the western parts of Awdal region with the goal of annexing Zeyla to Djibouti.[59][60] The SNM rejected their claims, and took military action against the USF soldiers, which were swiftly routed and violently crushed.[61][60]

In the post-independence period, Zeila was administered as part of the official Awdal region of Somaliland.

Following the outbreak of the civil war in the early 1990s, much of the city's historic infrastructure was destroyed and many residents left the area. However, remittance funds sent by relatives abroad have contributed toward the reconstruction of the town, as well as the local trade and fishing industries.

Demographics

The town of Zeila is primarily inhabited by people from the Somali ethnic group, with the Gadabuursi subclan of the Dir especially well represented.[62][63][64][65] The Issa subclan of the Dir are especially well represented in the wider Zeila District.[66]

Tim Glawion (2020) describes the clan demographics of both the town of Zeila and the wider Zeila District:

"Three distinct circles can be distinguished based on the way the security arena is composed in and around Zeila: first, Zeila town, the administrative centre, which is home to many government institutions and where the mostly ethnic Gadabuursi/Samaron inhabitants engage in trading or government service activities; second, Tokhoshi, an artisanal salt mining area eight kilometres west of Zeila, where a mixture of clan and state institutions provide security, and two large ethnic groups (Ciise and Gadabuursi/Samaron) live alongside one another; third the southern rural areas, which are almost universally inhabited by the Ciise clan, with its long, rigid culture of self-rule."[67]

Elisée Reclus (1886) describes the two main ancient routes leading from Harar to Zeila, one route passing through the country of the Gadabuursi and one route passing through Issa territory. The author describes the town of Zeila and its immediate environs as being inhabited by the Gadabuursi, whereas the wider Zeila District and countryside south of the town, as being traditional Issa clan territory:

"Two routes, often blocked by the inroads of plundering hordes, lead from Harrar to Zeila. One crosses a ridge to the north of the town, thence redescending into the basin of the Awash by the Galdessa Pass and valley, and from this point running towards the sea through Issa territory, which is crossed by a chain of trachytic rocks trending southwards. The other and more direct but more rugged route ascends north-eastwards towards the Darmi Pass, crossing the country of the Gadibursis or Gudabursis. The town of Zeila lies south of a small archipelago of islets and reefs on the point of the coast where it is hemmed in by the Gadibursi tribe. It has two ports, one frequented by boats but impracticable for ships, whilst the other, not far south of the town, although very narrow, is from 26 to 33 feet deep, and affords safe shelter to large craft."[68]

References

- ^ Somalia City & Town Population. Tageo.com. Retrieved 2020-03-18.

- ^ "Somalia City & Town Population" (PDF). FAO. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 February 2015. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ^ François-Xavier Fauvelle-Aymar, "Desperately Seeking the Jewish Kingdom of Ethiopia: Benjamin of Tudela and the Horn of Africa (Twelfth Century)", Speculum, 88.2 (2013): 383–404.

- ^ G. W. B. Huntingford (ed.), The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, by an Unknown Author: With Some Extracts from Agatharkhides ‘On the Erythraean Sea’ (Ashgate, 1980), p. 90.

- ^ Lionel Casson (ed.), The Periplus Maris Erythraei: Text with Introduction, Translation and Commentary (Princeton University Press, 1989), pp. 116–17. Avalites may be Assab or a village named Abalit near Obock.

- ^ Historical Dictionary of Somalia by Mohamed Haji Mukhtar page 268

- ^ Futūḥ al-Ḥabasha. (n.d.). Christian-Muslim Relations 1500 – 1900. doi:10.1163/2451-9537_cmrii_com_26077

- ^ Glawion, Tim (2020-01-30). The Security Arena in Africa: Local Order-Making in the Central African Republic, Somaliland, and South Sudan. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-65983-3.

Three distinct circles can be distinguished based on the way the security arena is composed in and around Zeila: first, Zeila town, the administrative centre, which is home to many government institutions and where the mostly ethnic Gadabuursi/Samaron inhabitants engage in trading or government service activities; second, Tokhoshi, an artisanal salt mining area eight kilometres west of Zeila, where a mixture of clan and state institutions provide security and two large ethnic groups (Ciise and Gadabuursi/Samaron) live alongside one another; third the southern rural areas, which are almost universally inhabited by the Ciise clan, with its long, rigid culture of self-rule.

- ^ Reclus, Elisée (1886). The Earth and its Inhabitants The Universal Geography Vol. X. North-east Africa (PDF). J.S. Virtue & Co, Limited, 294 City Road.

Two routes, often blocked by the inroads of plundering hordes, lead from Harrar to Zeila. One crosses a ridge to the north of the town, thence redescending into the basin of the Awash by the Galdessa Pass and valley, and from this point running towards the sea through Issa territory, which is crossed by a chain of trachytic rocks trending southwards. The other and more direct but more rugged route ascends north-eastwards towards the Darmi Pass, crossing the country of the Gadibursis or Gudabursis. The town of Zeila lies south of a small archipelago of islets and reefs on a point of the coast where it is hemmed in by the Gadibursi tribe. It has two ports, one frequented by boats but impracticable for ships, whilst the other, not far south of the town, although very narrow, is from 26 to 33 feet deep, and affords safe shelter to large craft.

- ^ UN (1999) Somaliland: Update to SML26165.E of 14 February 1997 on the situation in Zeila, including who is controlling it, whether there is fighting in the area, and whether refugees are returning. "The Gadabuursi clan dominates Awdal region. As a result, regional politics in Awdal is almost synonymous with Gadabuursi internal clan affairs." p. 5.

- ^ McClanahan, Sheppard & Obura 2000, p. 273.

- ^ Trimingham, J. Spencer (13 September 2013). Islam in Ethiopia. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781136970290.

- ^ Divine Fertility: The Continuity in Transformation of an Ideology of Sacred Kinship in Northeast Africa by Sada Mire Page 129

- ^ "Zeila: Beneath the Ruins of Ancient Civilization". Maroodi Jeex: A Somaliland Alternative Journal (10). 1998. Archived from the original on 2001-06-29.

- ^ Journal of African History pg.50 by John Donnelly Fage and Roland Anthony Oliver

- ^ a b Mohamed Diriye Abdullahi, Culture and Customs of Somalia, (Greenwood Press, 2001), pp.13–14

- ^ Wilfred Harvey Schoff, The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea: travel and trade in the Indian Ocean, (Longmans, Green, and Co., 1912) p.25

- ^ Briggs, Phillip (2012). Somaliland. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 7. ISBN 978-1841623719.

- ^ a b Encyclopedia Americana, Volume 25. Americana Corporation. 1965. p. 255.

- ^ a b Lewis, I.M. (1955). Peoples of the Horn of Africa: Somali, Afar and Saho. International African Institute. p. 140.

- ^ Fage, J. D.; Oliver, Roland; Oliver, Roland Anthony; Clark, John Desmond; Gray, Richard; Flint, John E.; Roberts, A. D.; Sanderson, G. N.; Crowder, Michael (1975). The Cambridge History of Africa. Vol. 3. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521209816.

- ^ Said M-Shidad Hussein, The Somali Calendar: An Ancient, Accurate Timekeeping SystemSomali calendar

- ^ Insoll, Timothy (3 July 2003). The Archaeology of Islam in Sub-Saharan Africa. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521657020.

- ^ Jamāl al-Dīn Abī Muḥammad ʿAbd Allāh b. Yūsuf al-Zaylaʿī al-Ḥanafī (2018) Naṣb al-Rāya li-Aḥādīth al-Hidāya. 2 vols. (Beirut: Dār Ibn Ḥazm).

- ^ a b c I. M. Lewis, A pastoral democracy: a study of pastoralism and politics among the Northern Somali of the Horn of Africa, (LIT Verlag Münster: 1999), p.17

- ^ Rayne, Henry A. Sun, sand and somals : leaves from the note-book of a district commissioner in British Somaliland. London : Witherby. (1921). https://archive.org/stream/sunsandsomalslea00raynuoft/sunsandsomalslea00raynuoft_djvu.txt

- ^ Houtsma, M. Th (1987). E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913–1936. BRILL. pp. 125–126. ISBN 9004082654.

- ^ mbali, mbali (2010). "Somaliland". Basic Reference. 28. London, UK: mbali: 217–229. doi:10.1017/S0020743800063145. S2CID 154765577. Archived from the original on 2012-04-23. Retrieved 2012-04-27.

- ^ Briggs, Philip (2012). Bradt Somaliland: With Addis Ababa & Eastern Ethiopia. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 10. ISBN 978-1841623719.

- ^ a b Lewis, I. M. (1999). A Pastoral Democracy: A Study of Pastoralism and Politics Among the Northern Somali of the Horn of Africa. James Currey Publishers. p. 17. ISBN 0852552807.

- ^ Jeremy Black, Cambridge Illustrated Atlas, Warfare: Renaissance to Revolution, 1492–1792, (Cambridge University Press: 1996), p.9.

- ^ Fage, J. D.; Oliver, Roland (1975-01-01). The Cambridge History of Africa. Cambridge University Press. p. 153. ISBN 9780521209816.

- ^ I. M. Lewis (1959) "The Galla in Northern Somaliland" (PDF).

- ^ "Ibn Majid". Medieval Science, Technology, and Medicine: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. 2005. ISBN 978-1-135-45932-1.

- ^ "There is an abundance of provisions in this city, and there are many merchants here." The Travels of Ludovico di Varthema in Egypt, Syria, Arabia Deserta and Arabia Felix, in Persia, India, and Ethiopia, A.D. 1503 to 1508, translated by John Winter Jone, and edited by George Percy Badger (London: the Hakluyt Society, 1863), p. 87

- ^ Pankhurst, Richard (1982). History of Ethiopian towns from the Middle Ages to the early nineteenth century. Steiner. p. 63. ISBN 3515032045.

- ^ Dames, L., 1918: The Book of Duarte Barbosa London: Hakluyt Society

- ^ Abir, Mordechai (1968). Ethiopia: The Era of the Princes; The Challenge of Islam and the Re-unification of the Christian Empire (1769–1855). London: Longmans. p. 15. Abir defines the Sahil as "the coast," which stretched from the Gulf of Tadjoura to Cape Guardafui

- ^ Abir, Era of the Princes, p. 14

- ^ Abir, Era of the Princes, p. 16

- ^ Making Sense of Somali History: Volume 1 - Page 63

- ^ Omar, Mohamed Osman (2001). The scramble in the Horn of Africa: history of Somalia, 1827-1977. Somali Publications. ISBN 9781874209638.

- ^ Rayne, Major.H (1921). Sun, Sand and Somals - Leaves from the Note-Book of a District Commissioner. Read Books Ltd. p. 75. ISBN 9781447485438.

- ^ Abir, Mordechai (1968). Ethiopia: the era of the princes: the challenge of Islam and reunification of the Christian Empire, 1769–1855. Praeger. p. 18. ISBN 9780582645172.

- ^ I.M. Lewis, A Modern History of the Somali, fourth edition (Oxford: James Currey, 2002), p.43 & 49

- ^ Charton, Edouard (1862). Le tour du monde: nouveau journal des voyages, Volume 2; Volume 6 (in French). Libraires Hachette. p. 78.

- ^ E. H. M. Clifford, "The British Somaliland-Ethiopia Boundary," Geographical Journal, 87 (1936), p. 289

- ^ Henry, J. (1885). Traité de protectorat de la France sur les territoires du pays des Gada-boursis. Ministère des Colonies-Traités (1687-1911).

- ^ Henry, J. (1885). Traité de protectorat de la France sur les territoires du pays des Gada-boursis. Ministère des Colonies-Traités (1687–1911).

- ^ Hess, Robert L. (1979). Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Ethiopian Studies, Session B, April 13-16, 1978, Chicago, USA. Office of Publications Services, University of Illinois at Chicago Circle.

- ^ Hess, Robert L. (1979). Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Ethiopian Studies, Session B, April 13-16, 1978, Chicago, USA. Office of Publications Services, University of Illinois at Chicago Circle.

- ^ Lewis, I. M. (1988). A Modern History of Somalia (PDF). Westview Press.

By the end of 1885 Britain was preparing to resist an expected French landing at Zeila. Instead, however, of a decision by force, both sides now agreed to negotiate. The result was an Anglo-French agreement of 1888 which defined the boundaries of the two protectorates as between Zeila and Jibuti: four years later the latter port became the official capital of the French colony.

- ^ Simon Imbert-Vier, Frontières et limites à Djibouti durant la période coloniale (1884–1977), Université de Provence, Aix-Marseille, 2008, p. 81.

- ^ a b Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 950.

- ^ Rayne, Henry A. (1921). Sun, sand, and Somals; leaves from the note-book of a district commissioner in British Somaliland. University of California Libraries. London : Witherby.

- ^ "Die geistige cultur der Danâkil, Galla und Somâl, nebst nachträgen zur materiellen cultur dieser völker". p. 171.

To my Beloved: "Ancient song of the Zeilans (Ahl Zeila), a mixture of Arabs, Somâli, Abyssinians and Negroes, which Major J. S. King dictated to a hundred-year-old man in 1886. The song was incomprehensible to the Somâl. It is undoubtedly written by a Gadaburssi and addressed to a girl of the same tribe.

- ^ "Die geistige cultur der Danâkil, Galla und Somâl, nebst nachträgen zur materiellen cultur dieser völker". p. 171-172.

- ^ Prunier, Gérard (2021). The Country that Does Not Exist: A History of Somaliland. Oxford University Press. p. 137. ISBN 978-1-78738-203-9.

- ^ a b Berdún, Maria Montserrat Guibernau i; Guibernau, Montserrat; Rex, John (2010-01-11). The Ethnicity Reader: Nationalism, Multiculturalism and Migration. Polity. ISBN 978-0-7456-4701-2.

- ^ a b Gurdon, Charles (1996). "The Horn of Africa". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 59 (1): 63. doi:10.1017/S0041977X0002927X. ISSN 1474-0699.

- ^ Gebrewold, Belachew (2016-04-15). Anatomy of Violence: Understanding the Systems of Conflict and Violence in Africa. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-18139-2.

- ^ Glawion, Tim (2020-01-30). The Security Arena in Africa: Local Order-Making in the Central African Republic, Somaliland, and South Sudan. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-65983-3.

Three distinct circles can be distinguished based on the way the security arena is composed in and around Zeila: first, Zeila town, the administrative centre, which is home to many government institutions and where the mostly ethnic Gadabuursi/Samaron inhabitants engage in trading or government service activities; second, Tokhoshi, an artisanal salt mining area eight kilometres west of Zeila, where a mixture of clan and state institutions provide security and two large ethnic groups (Ciise and Gadabuursi/Samaron) live alongside one another; third the southern rural areas, which are almost universally inhabited by the Ciise clan, with its long, rigid culture of self-rule.

- ^ Reclus, Elisée (1886). The Earth and its Inhabitants The Universal Geography Vol. X. North-east Africa (PDF). J.S. Virtue & Co, Limited, 294 City Road.

Two routes, often blocked by the inroads of plundering hordes, lead from Harrar to Zeila. One crosses a ridge to the north of the town, thence redescending into the basin of the Awash by the Galdessa Pass and valley, and from this point running towards the sea through Issa territory, which is crossed by a chain of trachytic rocks trending southwards. The other and more direct but more rugged route ascends north-eastwards towards the Darmi Pass, crossing the country of the Gadibursis or Gudabursis. The town of Zeila lies south of a small archipelago of islets and reefs on the point of the coast where it is hemmed in by the Gadibursi tribe. It has two ports, one frequented by boats but impracticable for ships, whilst the other, not far south of the town, although very narrow, is from 26 to 33 feet deep and affords safe shelter to large craft.

- ^ Samatar, Abdi I. (2001) "Somali Reconstruction and Local Initiative: Amoud University," Bildhaan: An International Journal of Somali Studies: Vol. 1, Article 9, p. 132.

- ^ Battera, Federico (2005). "Chapter 9: The Collapse of the State and the Resurgence of Customary Law in Northern Somalia". Shattering Tradition: Custom, Law and the Individual in the Muslim Mediterranean. Walter Dostal, Wolfgang Kraus (ed.). London: I.B. Taurus. p. 296. ISBN 978-1-85043-634-8. Retrieved 18 March 2010.

Awdal is mainly inhabited by the Gadabuursi confederation of clans.

- ^ Renders, Marleen; Terlinden, Ulf (13 October 2011). "Chapter 9: Negotiating Statehood in a Hybrid Political Order: The Case of Somaliland". In Tobias Hagmann; Didier Péclard (eds.). Negotiating Statehood: Dynamics of Power and Domination in Africa. Wiley. p. 191. ISBN 9781444395563. Retrieved 21 January 2012.

- ^ Glawion, Tim (2020-01-30). The Security Arena in Africa: Local Order-Making in the Central African Republic, Somaliland, and South Sudan. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-65983-3.

Three distinct circles can be distinguished based on the way the security arena is composed in and around Zeila: first, Zeila town, the administrative centre, which is home to many government institutions and where the mostly ethnic Gadabuursi/Samaron inhabitants engage in trading or government service activities; second, Tokhoshi, an artisanal salt mining area eight kilometres west of Zeila, where a mixture of clan and state institutions provide security and two large ethnic groups (Ciise and Gadabuursi/Samaron) live alongside one another; third the southern rural areas, which are almost universally inhabited by the Ciise clan, with its long, rigid culture of self-rule.

- ^ Reclus, Elisée (1886). The Earth and its Inhabitants The Universal Geography Vol. X. North-east Africa (PDF). J.S. Virtue & Co, Limited, 294 City Road.

Two routes, often blocked by the inroads of plundering hordes, lead from Harrar to Zeila. One crosses a ridge to the north of the town, thence redescending into the basin of the Awash by the Galdessa Pass and valley, and from this point running towards the sea through Issa territory, which is crossed by a chain of trachytic rocks trending southwards. The other and more direct but more rugged route ascends north-eastwards towards the Darmi Pass, crossing the country of the Gadibursis or Gudabursis. The town of Zeila lies south of a small archipelago of islets and reefs on a point of the coast where it is hemmed in by the Gadibursi tribe. It has two ports, one frequented by boats but impracticable for ships, whilst the other, not far south of the town, although very narrow, is from 26 to 33 feet deep, and affords safe shelter to large craft.

Sources

- McClanahan, T. R.; Sheppard, C. R. C.; Obura, D. O. (2000). Coral Reefs of the Indian Ocean: Their Ecology and Conservation. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-195-35217-3.